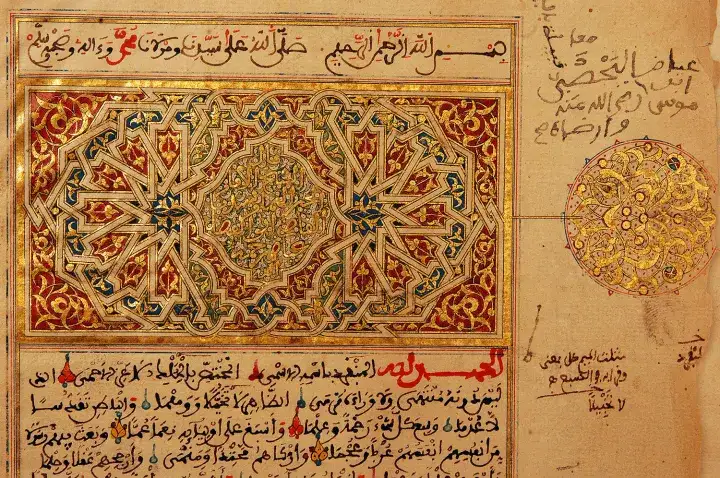

Deep inside the Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu, a quiet revolution is unfolding. One fragile page at a time, centuries-old books are being photographed, scanned, and brought back to life after surviving war, fire, and exile.

The Great Escape of 2012

When al-Qaeda-linked militants overran the city thirteen years ago, local families and institute workers refused to let this priceless heritage burn.

In a secret night-time operation, they packed more than 300,000 manuscripts into metal trunks and smuggled them hundreds of kilometres south to safety in Bamako. Many were hidden under vegetables, clothes, or carried on river canoes. It was one of the greatest cultural rescues in modern history.

Now, after years of digitisation and careful restoration, most of the collection has finally come home.

A Library Unlike Any Other on Earth

These are not just old books they are the lost memory of West Africa.

You’ll find:

- Medical guides describing cataract surgery performed centuries before Europe claimed the technique

- Astronomy charts that mapped the stars from the Sahara

- Legal rulings that lowered bride prices so poor men could marry

- Heated debates about whether smoking tobacco is sinful

- Personal letters, earthquake reports, and family trees of scholars stretching back a thousand years

Some pages still smell of smoke from the 2012 fires. Empty spaces on the shelves remind everyone that a few volumes are still missing or quietly sold by families who can no longer afford to keep them.

Rewriting History, One Page at a Time

Dr Mohamed Diagayaté, the institute’s director, says simply: “Everything written here about Timbuktu, Macina, Mopti you won’t find it anywhere else in the world.”

Local heritage guardian Sane Chirfi Alpha points to one astonishing story buried in the texts: a Timbuktu physician who allegedly travelled to France and cured a crown prince when European doctors failed effectively saving the French throne.

Keeping the Chain of Knowledge Alive

Every manuscript carries a “chain of transmission” a handwritten family tree showing exactly which scholar taught which student, all the way back to the original author. This tradition is now being passed to a new generation.

Twenty-four-year-old Baylaly Mahamane is one of the young trainees. “I want to master this work,” he says. “These books teach us medicine, history, how our ancestors lived. If we lose them, we lose ourselves.”

Danger Still Lurks Outside the Walls

The jihadist threat has not vanished. Armed groups still control parts of northern Mali. Roads get blocked, researchers cancel trips, and some foreign scholars refuse to visit. Security fears slow down the work that only experts can do in person.

Yet inside the institute, the lights stay on late. Staff keep scanning, cataloguing, and teaching. Across the city, coloured bulbs are going up around the great Sankoré Mosque for Mawlid proof that Timbuktu’s soul is still very much alive.

For the guardians of these manuscripts, the mission is clear: protect the written proof that West Africa was once and can be again one of the world’s great centres of learning.

ACS and BlackRock Launch €2B Data Center Partnership to Power AI Boom